Why you should care (and what IS the Higgs Boson Anyway?)

The probable discovery last month of the Higgs boson by a large team of physicists at CERN has been hailed by scientists and the public. Predicted by Peter Higgs over fifty years ago, this particle was needed to explain a key puzzle in the “Standard Model” of particle physics. There have been hundreds of articles about this discovery in the popular press, but none of the ones I have seen have adequately addressed what I think is the key question about the finding, namely: Who Cares?

Let me tell you why the discovery matters.

First let me explain why the widely advertised reason – that it shows physical theory is on track – is not convincing. Of course it is a source of pride to know that the theory works. But if the Higgs had not been found today, scientists would just have looked elsewhere (that is, in more energetic collisions). And if the Higgs were to have remained undetected through another decade of experiments, then a revised model of particle physics would have been proposed. (Several were already under discussion just in case.) The point is that modern science and its successes do not rise or fall on the discovery of the Higgs — only certain of its particular theories do.

Do you care whether there is supersymmetry, as predicted in current models? Or even whether there is a single Grand Unified Theory of physics (“Let There Be Light,” p. 94)? I doubt it. Most people, if they think about it at all, probably regard the success of theories as recondite matters for experts. People care rather that we make progress in our understanding of nature, and the details are irrelevant.

But they should care.

The Higgs boson is one of the lynchpins in the current “standard model” of physics that is in turn the basis for models of the big bang creation. The “inflationary universe” (LTBL, p.81) presumes the standard model when it posits a mechanism whereby the vacuum suddenly erupts to create the universe in a big bang, and then spontaneously decays (at least in our universe) to produce the cosmos we actually live in. Without a Higgs, the inflation scenario would be much more tentative.

(For the record, in 1993 publishers made up the extraneous title “The God Particle” for the new book about the Higgs by Leon Lederman, the Nobel prize-winning particle physicist. This meaningless hyperbole helped the name stick, but no scientist was happy about the pitch and many have complained.)

Elsewhere in these webpages I discuss the concept of “many universes” in the context of the Anthropic Principle. In brief, all scientists agree that the universe is amazingly, precisely fine-tuned to enable intelligent life. Only two reasons have been proposed to explain this spectacular good luck: God and a purposeful creation, or random chance and a multiverse (a nearly-infinite number of universes). The second depends on current physical theories, and if the Higgs were not found, or if the current theories are wrong, then the proposed mechanisms for making a multiverse are also wrong. True, if it had not been discovered today it might have been found at some higher energy, or else some other theory would come along to explain the results. But these other cases might not have allowed for quite the same big bang production of a multiverse.

In short, the Higgs boson has something to say about how we see ourselves in the universe: as creatures with meaning and purpose, or not. Its discovery therefore reaffirms the choice, and sharpens the issue for both religious and non-religious people.

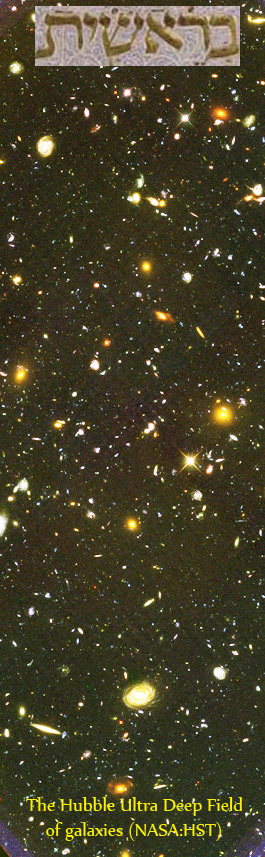

One last point about what we know and don’t know. About 90% (!) of the matter in the universe is still mysterious – the dark matter (LTBL, page 70). We do not know what it is, what kind of particle(s) it contains, or if or how the Higgs interacts with it. Everything in our normal world, including the Higgs, represents only a tiny fraction of everything. And when it comes to the overall behavior of the universe, dark matter is only about 1/3 as significant as dark energy, the similarly mysterious quantity that is causing the acceleration of the cosmos (LTBL, page 83). The Higgs is just a part of a very much larger story that remains the biggest puzzle in astronomy and physics. Who knows what a complete theory will bring?

I began by observing that popular discussions of the Higgs have not explained why it matters. While I’m at it, let me also observe that the articles I have seen do not explain what the Higgs boson actually is! Let me try to summarize it in a few lines. First of all, a boson (LTBL, page 64) is a particle that aggregates; that is, it tends to group with other bosons. Photons (particles of light) are the most common bosons. The second, and only other kind of particle in the universe, is the fermion. A fermion (op cit.) is the opposite: it tends to segregate, that is, only one fermion can be in a particular state at a time. Electrons and protons – normal matter – are fermions. Bosons also play a special role: each of the four forces in the universe are transmitted by bosons (LTBL, page 57). Photons carry the electromagnetic force, gravitons carry gravity, gluons carry the strong force, and the vector bosons are involved in the weak force. Some bosons have no (rest) mass, like the photon, and travel at the speed of light; the Higgs boson does have mass, and although it does not carry a force, it does play the role of giving mass to particles.

The reason for there being only bosons and fermions in the world, and also the reason why particles can be organized into groups and subgroups, is crucial to understand. Our world runs by quantum mechanics (why this is, is another mystery). In a quantum mechanical world, where particles are also waves, their symmetry determines their properties (LTBL, page 92; 156). Bosons aggregate because they are symmetric, which is to say that when its features are flipped, it looks the same. Like water waves whose overlapping crests merge and grow larger, bosons aggregate. Fermions segregate because they are antisymmetric, and when their features are flipped they appear opposite, and like crests of oppositely moving water waves, they cancel out – thus no two can be in the same place.

The discovery of the Higgs boson should prompt us all to pause and admire what we know, to acknowledge what we do not know, and to appreciate that regardless of how our universe came to be, how it works, or where it is headed, we live in a blessed state that calls for our awareness and caring. Our relationship with God is longer based on our ignorance of the details the Creation, but instead on this compassionate awareness.