Messier 51, the Whirlpool Galaxy (credit: NASA and Hubble Space Telescope)

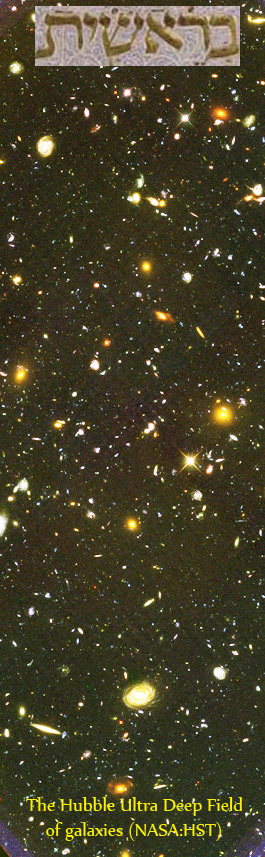

The Size of the Universe

After my Op-Ed column in the Forward newspaper, “In the Beginning, 13.73 billion years ago…” , people wrote to ask how a universe that is only 13.7 billion years old can have a “current dimension of about 46 billion light-years”?

The short answer is that the universe is not static. If it were, then indeed the most distant realms we could see would be the ones whose light departed 13.7 billion years ago, namely, those 13.7 billion light-years away. As the universe ages, we would be able to see more and more distant regions.

But the universe is expanding. Light from remote galaxies has been traveling towards us, in some cases for over ten billion years, and during that long time those galaxies have moved farther away from us. The current distance of the farthest regions, assuming the expansion follows the most commonly accepted interpretation, is about 46 billion light-years.

In these and all other scenarios, though, we have no idea what the “real” dimension of the universe is. It might be much (much!) larger than the universe we can measure. Why not? In these and all those other reasonable scenarios, however, the age of the universe is well determined at about 13 billion years old, because all the regions — in particular the ones we can study — are presumably the same age.

Chapters 2 and 5 of Let There Be Light describe the non-intuitive expansion of space in more detail; also be sure to check the explanatory comment on page 239.

What came before the Big Bang?

Numerous readers wrote to ask me what came before the big bang, the event about 13.73 billion years ago that led to the universe as we know it. I was interested to note that all of the questioners so far have been religiously inclined, and seemed to ask the question in the spirit (unstated, however) of probing whether God had a role to play in setting this great process into motion. Of course, even athiests could be asking this question, but perhaps they feel less comfortable asking what might be seen as a meaningless question. My preliminary comment is therefore to reassure you that the question is a perfectly fair one, and as I discuss in Chapter 9 (“Before and After”), many physical (and religious) ideas have been put forward to address it.

The most familiar notion is that of a eternally bouncing universe, that is, a universe that has enough matter to be gravitationally “closed” and expand only for a while — it ultimately contracts because of gravity until it shrinks to a point and rebounds again in another big bang. It now appears from the data we have that this option is ruled out: there is just not enough matter present, even including effects of “dark matter” (Chapter 4). A more radical idea is that of a universe in which time itself began in the big bang, a concept originally developed by Stephen Hawking and James Hartle.

A novel and relatively new approach comes from attempts to explain the wondrous, even miraculous suitablility of the universe for intelligent life by invoking purely natural processes. This “many-worlds” analysis argues that there are an infinite (or nearly infinite) number of new universes continuously being created from the vacuum, each with different sets of physical properties. Only in the few universes perfectly suitable for life will life develop. A consequence of this approach is that universes are constantly being created, effectively for eternity as far as is known.

The Rabbis of the Talmud (and, following their lead, the Kabbalists) speculated at length on what came before “In the beginning.” In one view, the governing principles of the universe (the nature of matter, cause and effect, etc.) were present before the creation.